Introduction:

When a foreign applicant or company signs a Power of Attorney in China, they are, in effect, legally transferring the right to register the trademark to a local Chinese agency. However, this crucial step is often overlooked. Many foreign applicants receive POA templates via email, WhatsApp, or other platforms, where the sender may claim to be a “Chinese trademark agency.” In reality, the applicant has never seen the formal company name, business license, or even verified whether the company truly exists.

Of course, a legitimate Chinese licensed trademark agency must be a lawfully registered entity in mainland China — such as a company, partnership, or law firm — and must be officially filed with CNIPA.. In many cases, foreign-based trademark service companies are simply third-party intermediaries who eventually transfer the case to a real Chinese agent. This creates a significant legal and procedural risk.

I. Who Are You Really Authorizing? Understanding the Power of Attorney in China

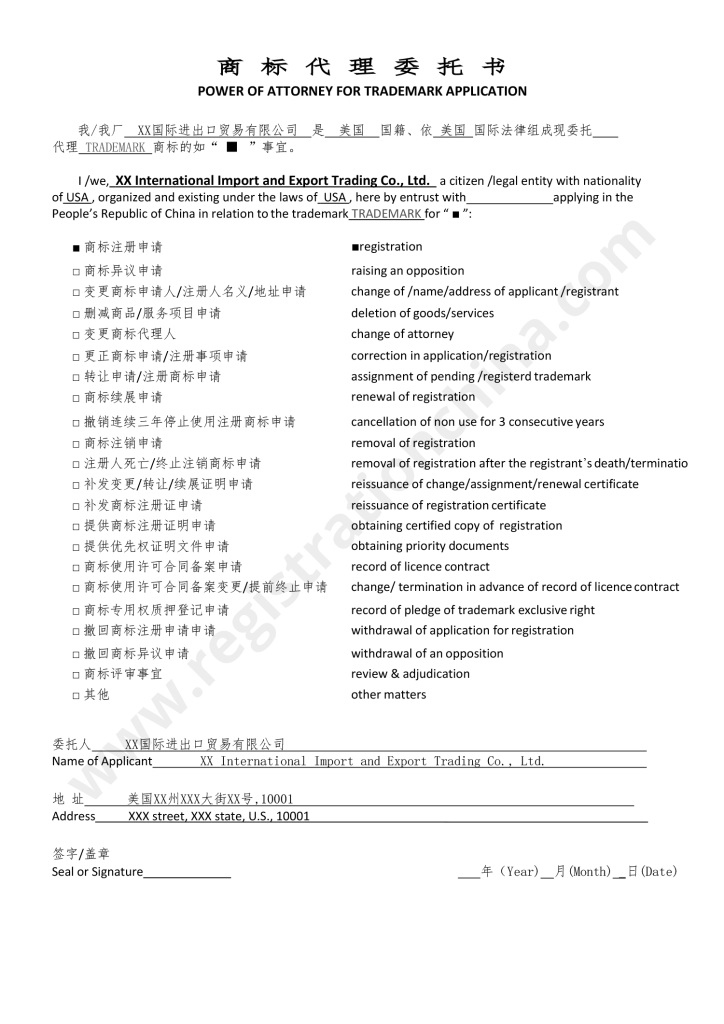

The POA is a legally binding document. When using a bilingual format (Chinese-English), it must:

-

Clearly state the authorized party’s Chinese name and English name.

-

Include precise language of authorization, such as:

“Hereby entrust with GWBMA applying in the People’s Republic of China”; -

Specify that the authorized entity is a Chinese-registered company with an official CNIPA filing record.

Without this, the authorization may not be legally valid.

It’s important to note that the CNIPA filing is conducted under the Chinese name of the agency only; English names do not appear in official records. However, there must be a verifiable and transparent connection between the Chinese and English names.

If the authorized entity listed in the POA is a foreign company, an unregistered organization, or a firm without a valid Chinese business registration and CNIPA filing, then even if the trademark application is initially submitted, the applicant may face serious legal risks during later stages such as enforcement, transfer, or response to office actions.

In short: what you’re signing is not just a document—you’re handing over the fate of your trademark to someone. The key is: to whom?

II. What Is a Valid Power of Attorney in China?

According to the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA), foreign applicants must appoint a trademark agency that is registered and officially filed in mainland China to submit trademark applications.

In practice, some foreign applicants rely on overseas trademark service providers. However, these companies are often intermediaries that do not have the legal capacity to file directly with CNIPA, and must eventually forward the case to a licensed Chinese agent.

This intermediary structure is not necessarily illegal, but the POA must clearly specify who the final authorized Chinese agency is, rather than just listing the foreign intermediary. Failing to do so may cause the trademark owner to misunderstand the true authorized party, leading to legal uncertainties and difficulties in asserting rights.

Unless the foreign service provider uses the Madrid International Registration System (International Trademark Classification / Madrid System), it cannot bypass the CNIPA authorization process. But even this alternative has serious limitations.

The Madrid route involves WIPO’s transmission and notification procedures, which typically take 1–2 months before the case even enters the Chinese examination stage. Coupled with CNIPA’s own examination timeline, the total processing time is often longer than a direct filing through a local Chinese agent.

Currently, even when filed through a qualified Chinese agent, a foreign application usually takes around six months to receive a preliminary approval. The Madrid system often extends that to nine months or more, with less efficient communication throughout the process.

Moreover, even if a Madrid-based trademark is successfully registered, any further actions — such as corrections, oppositions, renewals, or assignments — must still be handled within China by a local agent.

For this reason, foreign applicants seeking a faster, more secure, and cost-effective registration process should directly authorize a CNIPA-registered local trademark agency through a POA.

III. Why a Bilingual POA Matters

Many foreign trademark applicants share the same concern when signing a Chinese POA:

they don’t fully understand what they are authorizing.

This is because most local Chinese agencies provide POAs in Chinese only, often titled simply “Trademark Agency Authorization Letter.” Non-Chinese-speaking applicants are left to “trust” the content without truly understanding the scope, duration, or legal boundaries of the authorization.

In international legal practice, comprehensibility is a prerequisite for enforceable authorization. It is especially essential in cases where:

-

The document must be submitted to the legal department at a corporate headquarters;

-

The applicant is a publicly listed company or has multiple directors requiring internal compliance review;

-

The trademark involves a global brand requiring multi-language legal documentation.

To solve this, GWBMA provides a standardized bilingual POA template, with each Chinese sentence paired directly with its English translation. Clients can verify all elements before signing, including:

-

Full legal name of the agency (in both Chinese and English);

-

Scope of authorization for filing and representation;

-

Whether it includes authority to respond to rejections or file oppositions;

-

The relationship between the signatory and the applicant entity (corporate or individual).

Power of Attorney in China

IV. Signature: A Legal Act, Not a Formality

In the POA, the signature is not a symbolic step—it determines the validity of the authorization itself.

-

It must be signed by the actual legal representative or trademark owner.

If the signatory is not the legal representative (for companies) or the actual trademark holder (for individuals), CNIPA may reject the authorization or require supplemental proof. -

The signature must match the applicant’s official name.

Especially for English names, consistency is critical.

For example, if the applicant is a company, we need the Certificate of Incorporation or equivalent registration document;

If the applicant is an individual, we need a valid passport.

Any discrepancy may lead to challenges during the application process. -

The signature must be clear and verifiable.

This includes:

-

Avoiding pasted or scanned image signatures (unless certified by a recognized e-signature system);

-

Using a black ink pen, with a clearly scanned document;

-

Including full signature date and location;

-

Ensuring multi-page POAs are signed on the final page, with no missing signatures in between.

In trademark disputes, office action replies, or administrative appeals, CNIPA or courts may request the full authorization trail. Every signature matters — it is your legal proof.

Conclusion:

The Power of Attorney in China is not just about paperwork — it is about respecting the client’s understanding and safeguarding the legal validity of every step.

GWBMA is a professional agency that has built a complete trademark registration system specifically for foreign clients.

With a robust automation platform and a fully bilingual team, we deliver end-to-end services with clarity and confidence.

To us, a POA is not just a document — it’s the start of the safest path for your brand in China.