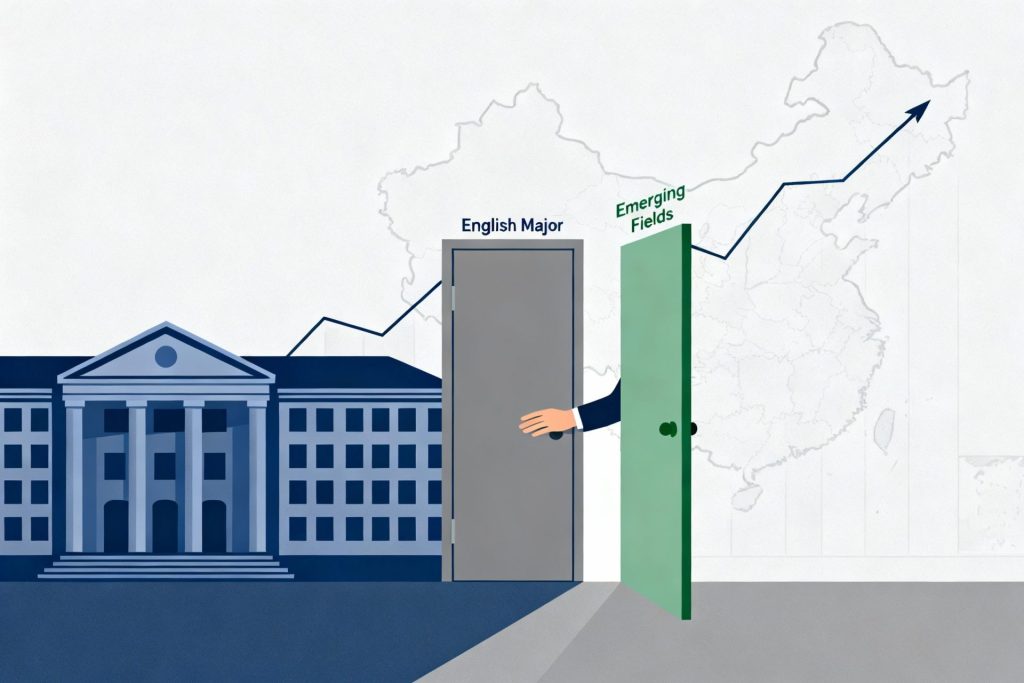

In recent years, a notable shift has rippled through China’s higher education landscape: universities across the country are phasing out English majors. This move, once unthinkable in an era where English proficiency was seen as a cornerstone of global competitiveness, reflects deeper changes in China’s geopolitical stance, economic priorities, and educational philosophy. As diplomatic tensions with Western countries persist and China solidifies its position as a global leader in technology and manufacturing, the role of English in academia is being reevaluated. This article examines the drivers behind the cancellation of English majors in China, the data supporting this trend, and what it means for students, educators, and international businesses.

The Geopolitical Backdrop: Shifting Ties and National Identity

The cancellation of English majors cannot be disentangled from China’s evolving relations with Western nations. Trade wars, diplomatic disputes, and technological competition have strained ties with countries like the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom—once primary destinations for Chinese students and key partners in academic exchange. In response, policymakers and educators have begun to reassess the emphasis on English, which is increasingly viewed through the lens of cultural and ideological influence. The Economist notes that legislators have sought to “limit the amount of time devoted to the study of English” and reduce its weight in university-entrance exams, signaling a broader push to prioritize domestic values and educational autonomy.

This shift also aligns with China’s “dual circulation” strategy, which aims to boost domestic innovation and reduce reliance on foreign technology and expertise. As the country invests heavily in AI, renewable energy, and advanced manufacturing, the need for specialized technical skills has overshadowed the traditional prestige of language proficiency. For many universities, canceling English majors is not just about cutting costs but reallocating resources to fields deemed more critical to national development.

Economic Realities: From Language to Technical Expertise

China’s economic ascent has fundamentally altered the calculus for students and universities alike. Decades ago, English proficiency was a gateway to global opportunities, from studying abroad to securing high-paying roles in multinational corporations. Today, however, China’s own tech giants—such as Huawei, ByteDance, and Alibaba—dominate the domestic market, while its manufacturing sector leads in EVs, batteries, and consumer electronics. As LinkedIn analysis highlights, English no longer carries the “symbolic value it once did as a gateway to opportunity” when domestic industries offer abundant, well-paid careers.

This economic shift is reflected in enrollment data. According to federal statistics cited by the Press Democrat, the number of English majors in China dropped by nearly a third between 2011 and 2021. Meanwhile, majors in engineering, computer science, and business administration have seen steady growth. Universities are responding to student demand: with fewer applicants choosing English, institutions are redirecting faculty and funding to programs with higher enrollment and clearer career pathways.

Data Trends: The Decline of Humanities and Rise of STEM

The cancellation of English majors is part of a broader decline in humanities enrollment across China. Fields like history, philosophy, and foreign languages have struggled to compete with STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) disciplines, which are prioritized under national initiatives like “Made in China 2025.” A 2023 report by China’s Ministry of Education revealed that humanities majors now account for less than 15% of total undergraduate enrollment, down from 22% a decade ago.

| Major Category | Enrollment Growth (2011-2021) |

|---|---|

| English/Languages | -31% |

| Engineering | +42% |

| Computer Science | +67% |

| Business Administration | +28% |

This trend mirrors global patterns, but China’s pace is accelerated by state-driven educational policies. Universities are under pressure to align curricula with national economic goals, and English departments—once seen as bridges to the world—are now often viewed as redundant in a landscape focused on self-reliance. Even top-tier institutions like Peking University and Tsinghua University have downsized English programs, replacing them with interdisciplinary courses that combine language training with technical skills, such as “English for Engineering” or “Cross-Cultural Communication in Tech.”

Impact on Students and the Job Market

For current and prospective students, the end of standalone English majors is forcing a rethink of career plans. Many English majors are now pivoting to related fields: some pursue master’s degrees in international relations or translation, while others add minors in AI or data analytics to enhance employability. Employers, too, are shifting expectations. A 2024 survey by China’s Ministry of Human Resources found that only 8% of job postings in multinational companies now require a pure English degree, down from 23% in 2018. Instead, preference is given to candidates with “dual expertise”—for example, engineers who speak English or marketers with cross-cultural communication skills.

This shift has created new opportunities for skills-based training. Private language schools and online platforms like iTalki report a surge in demand for “practical English” courses tailored to specific industries, such as medical translation or tech documentation. For international businesses operating in China, the message is clear: while English remains useful for communication, local partners and employees are increasingly valued for their technical expertise and understanding of domestic markets.

The Future of English in Chinese Education

The cancellation of English majors does not signal the end of English education in China—rather, its transformation. English is increasingly being framed as a tool, not a discipline. Primary and secondary schools continue to teach English as a core subject, but with a greater focus on practical communication than literary analysis. At the university level, English departments are evolving into “language service centers” that support other programs, offering electives in business English, legal translation, or academic writing for STEM students.

Looking ahead, this trend may deepen as China’s global influence grows. With initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative requiring proficiency in languages like Russian, Arabic, and Portuguese, English could lose its status as the sole “global language” in Chinese academia. Universities may instead prioritize multilingualism, equipping students to engage with diverse markets without centering Western cultures.

For now, the cancellation of English majors stands as a powerful symbol of China’s confidence in its own path. As the country navigates a new era of geopolitical and economic competition, its educational choices reflect a desire to balance global engagement with self-reliance. For students and businesses worldwide, understanding this shift is key to navigating the opportunities and challenges of a rapidly changing global landscape.